That Time I Gave Up Mirrors for Lent

It was Ash Wednesday, 2014. My pastor thumbed a black ashen cross on my forehead, and in that moment, I determined that I would cover every mirror in our house. I wouldn’t look at myself again until the trumpets sounded under my country church steeple on Easter morning.

I gave up my reflection for Lent because I was tired.

I was tired of the self-degradation that we engage in as women. We tell ourselves that we’re not enough—or let our bathroom scales tell us that we’re too much.

I was tired of the photoshopping. And yet I have a confession: I was just as guilty. I justified my own sort of airbrushing when my face filled the iPhone screen. I deftly wielded Instagram filters so I could magically take five years off my face.

Maybe I gave up mirrors because I was plain tired of being a hypocrite. And maybe I knew that my daughters, ages 12 and 9 at the time, were old enough to know when I was talking a good game and when I was actually living what I believe.

Children are mighty fine accountability partners. They are also mirrors themselves, reflecting what they see in their parents. I had to ask myself, What am I really reflecting?

We’ve all seen news reports about preteen girls and eating disorders. Nearly 80 percent of 10-year-olds are afraid of being overweight, according to the National Eating Disorders Association.

Of course, we’re quick to point an accusing finger at the glossy covers on magazine stands. But what are we modeling in front of our own mirrors while our children watch?

I wonder how many times our children see us suck in our post-baby guts, scowl at our reflections, run away from cameras, or shake our heads in disbelief when someone pays us a compliment.

And then comes this study, conducted by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. The study reports that increasing numbers of people are going under the knife as a result of their dissatisfaction with “selfies.” The study found that “one in three facial plastic surgeons have seen an increase in requests for surgery due to [patients] being more self-aware of looks in social media.”

I haven’t considered plastic surgery to remedy my flaws, but I do have to ask myself, What message am I sending to my daughters about body image in more subtle ways?

As Christian parents, we are the main (or at least the first) influencers in guiding our children into having a positive self-image and developing a healthy understanding of their identity in Christ—loved and accepted, as is.

But now—perhaps more than ever in human history—we are being bombarded with opportunities for literal self-reflection. We feel the constant temptation to put our best face forward.

As Christians, we subscribe to the belief that we all bear the image of God. Our best faces are already put forward—not because of Clinique but because of a divine Creator. As parents, we have the responsibility to model what it means to be secure in our identities, not only spiritually but physically as well.

We have the responsibility to model what it means to be secure in our identities, not only spiritually but physically as well.

A few days before I began my mirror fast, I stumbled onto a lesson on self-image, quite accidentally. I was visiting New York City with my mother-in-law and sisters-in-law, and though I’m not a regular viewer of The Today Show, some of the women in our group wanted to stand outside the studio during the live taping.

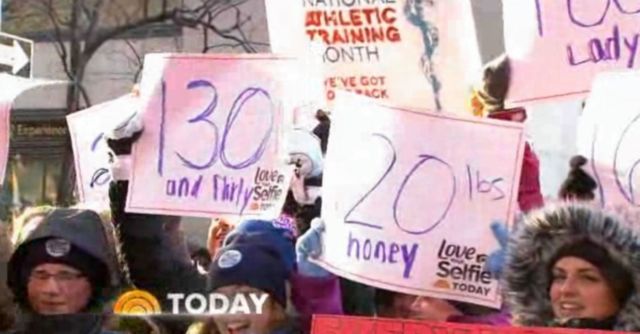

As we entered the spectator area, I was surprised to find a row of iPads, with which we were asked to take our selfies, filter-free. The photos would later be shown on national television as part of a weeklong series called “Love Your Selfie.” Dressed like Eskimos with fur-lined hoods cinched tightly around our heads, we mugged for a few self-portraits. And sure enough, we ended up on TV.

But it wasn’t the willingness to pose for unpolished selfies that surprised me as much as the signs. A few dozen women showed up outside the studio with Sharpied signs declaring their weight—150, 165, 185, 200.

I remembered then how, when my girls had asked me innocently a few days earlier how much I weighed, I had refused to tell them.

Standing outside The Today Show, I admired the freedom that the placard-holding women embodied. They seemed to embrace their whole selves, rather than cursing a series of parts.

I wanted that for myself, and I wanted that for my children—and for all of us as women.

There’s freedom in this place, where moms see our pouched midsections as proof that the gift of motherhood stretched us; where we admire our fine lines as marks of the years that have made us who we are.

A few days later I was back home in Iowa, looking in the mirror for the last time until Easter. I really took my reflection in—the whole of myself, not the parts.

And this time, I didn’t frown at the woman in the mirror. Not at all.

I didn’t chide or criticize her, and I resisted the urge to fret over the fact that she had a rather large pimple on her nose—at age 42.

I felt more tender about her than I usually did. I thought to myself, I need to love that woman better.

A day after I covered my mirrors, my younger daughter brushed up beside me in the bathroom while I was fumbling around with a flat-iron. She was watching her mother, as children do, and this time, I had given her an image that she wanted to reflect.

“Mommy,” she asked, “can you cover my mirrors? I don’t want you to do this alone.”

And like me, she didn’t look at her reflection until our Hope rose on Easter morn.

0 Comments