#TellHisStory: What It Really Means to Have Compassion

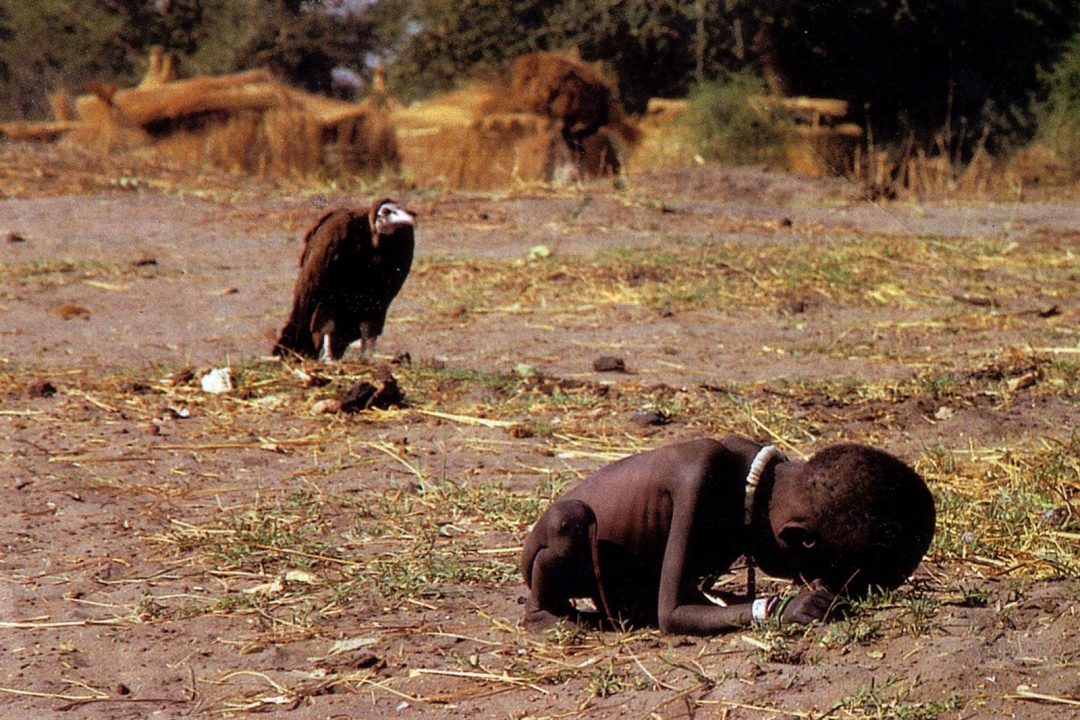

The museum was closing in half an hour, and I knew we wouldn’t want to miss the Pulitzer Prize Photography Gallery on the first floor. The gallery includes prints of every Pulitzer-Prize winning photograph taken since 1942. We moved slowly along the wall, lingering at each image, all of us hushed in remembrance.

The images are deeply etched into our world’s collective history and memory.

Then, one photo brought me to a full stop. I hadn’t seen it in years, and had forgotten about it, despite its horrendous imagery. I stood in front of it for several minutes, taking in every inch of agony, captured and framed in a quiet hallway in Washington, D.C.

At first I saw the emaciated child, crouched with her forehead to the ground. Her shoulder blades point skyward; her rib cage looks like prison bars.

You can’t look at the photo without wanting to jump behind the glass, to free her. You want to pick up the child and rescue her. She was trying to make it to a feeding center during Sudan’s famine, and collapsed right there. The world wept over this image.

Then, I looked behind the girl to see it: the plump vulture, so eager, so patient, waiting for the child to die.

Somewhere, in a place we can’t see, crouches the photographer, lens to eye.

It was 1993.

The photographer had found the girl when he heard a soft whimpering. He snapped frame after frame, hoping for the perfect picture. He told reporters later that he sat in his hiding spot for 20 minutes, quietly, so he wouldn’t scare off the vulture. He got his image, and then shooed the bird away.

But he didn’t pick up the child.

The New York Times ran the photo in March of that year. The reaction to the picture was strong. People were outraged when they learned that the photographer didn’t pick up the child and carry her to the feeding center. The New York Times later reported that the child had resumed her trek to the feeding center, and made it there on her own.

But the photographer told a friend, “I’m really, really sorry I didn’t pick the child up.”

Months later, the photographer, Kevin Carter, won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo.

He told an interviewer that after he won, he sat under a tree for a long time, “smoking cigarettes and crying.”

A few months later, he took his own life, leaving a note behind that said — “I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain . . . of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners . . . ”

I stood in front of that photo at the museum with a range of emotions coursing through my body:

First, I felt horror over the reality of famine in our world. The photo is 1993, but the problem is so very 2015.

I felt anger at the photographer, then pity and sadness, and also — perhaps oddly — gratitude, because in many ways, this one photo brought the plight of the Sudanese into full focus. One of Carter’s colleagues remarked that if it weren’t for that photo, “we wouldn’t know how to spell Sudan.”

But more than anything else, I felt a sense of inner conviction.

The words of Kevin Carter stir in my heart today: “I’m really, really sorry I didn’t pick the child up.”

I have to ask myself: Who have I failed to pick up?

Where have I watched the wounded through the lens, and after my twenty minutes were up, when did I walk away?

Right now, somewhere in the world, a child is bent over dying, while a vulture waits. Who will pick the child up?

Right now, somewhere in my country, a child is beaten down by poverty and abuse. Who will pick the child up?

Right now, somewhere in my community, a child is quietly crying out for someone to notice her. Who will pick the child up?

I don’t know if you or I will ever have an opportunity to pick up a Sudanese child, and carry her to the table. But right now, somewhere in our own corners of the world, we have the means to pick someone up, to invite them to the table, to carry them to a feast. If we know Jesus, we know where the feast is. And we know what our call is. To pick up crosses, and to pick up people.

Turn down any street, walk through any airport corridor, step through the doors of any hospital or church or schoolhouse, and you’ll see them: people who are begging that someone will pick them up.

Who will pick the child up today? Or the grieving widow? Or the cancer-ward patient? Or the homeless guy on the corner? Or the broken-down teenager in our own churches? Or the veteran suffering from PTSD?

I don’t want to be found, at the end of my life, to have been an observer in the wings, watching through lenses as horrors unfold. The lenses are my car windows, my computer screens, … my sunglasses.

I don’t want to be found, at the end of my life, with a prize that came with only earthly honor, and not Godly glory.

“I have always had it all at my feet,” read the last words of Kevin Carter’s suicide note. Sobering words for us all.

I don’t want my tombstone to read: “Here lies a woman who lived with good intentions, but died with deep regret.”

Kevin Carter’s photo, called Struggling Girl, is a clarion call for all of us to keep our eyes open for the sufferers — to feed the sufferers, to stand with the sufferers, to kneel with the sufferers, to carry the sufferers to the table of grace.

We weren’t meant to merely observe the sufferers; we are meant to suffer with them.

The word compassion is not a word of observation. It is a word of action. Compassion is a noun, but in the heart of a Christian, it ought to be a verb. The word compassion comes from the Latin stem compati meaning “suffer with.”

That afternoon at the museum, someone announced over the loudspeaker that it was time to go. The museum was closing.

Before I turned from the photo, I snapped a picture on my iPhone, to carry her with me … and to bring her to you. I want to always remember — God called me to be a picker-upper, a carrier, a woman whose compassion matched her conviction. I don’t ever want to forget that we are called to love as Jesus loved. I can’t forget that we have been carried by a Great Love who had compassion for us, who “suffered with,” who made compassion a verb on a cross.

What a tragedy, if we were to live this life having “always had it all at our feet,” but didn’t fully let it change our hearts for our fellow man.

I won’t forget you, little child. I won’t forget you. I have picked you up, and I have carried you home.

Sources:

July 7, 1994 article from the New York Times.

June 24, 2001, article from Time magazine.

Pulitzer Prize photo display at Newseum in Washington, D.C.

March 2, 2006, radio program on NPR.

Chapter 6 in The Global Journalist by Philip Seib.

August 15, 2006, column in the Chicago Tribune.

#TellHisStory

Hey Tell His Story crew! It’s always a joy to gather here every week. The linkup goes live each Tuesday at 4 p.m. (CT). If you would use the badge on your blog, found here, that would be great. And if you would visit at least one other blogger in the link-up and encourage them with a comment, that would be beautiful! Be sure to check the sidebar later. I’ll be featuring one of you over there! Our featured writer this week is Becky Keife. She is sharing the story behind a song she wrote in a Trader Joe’s parking lot. Find Becky here. To be considered as our featured writer, be sure to use our badge or a link to my blog from your post. 🙂 )

xo Jennifer

57 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- When My Prayers Seem Redundant | Waxing Gibbous - […] you just might find it here. I’m also linking up this week with Jennifer Dukes Lee at #TellHisStory and Holley…

- Worthy Sacrifices of Ordinary Days - […] @ Soul Survival, Intentional Tuesday, #RaRa Linkup, Testimony Tuesday, Titus 2 Tuesdays and #TellHisStory ~ I hope you’ll drop in…

- On Hard Days and Do-over Grace - Girl With Blog - […] few new-to-me linkups this week: #TellHisStory, A Mama Story, Tuesday Talk, Coffee for Your Heart, and Women with […]

- Endurance inspired by Hope - […] Sharing with Grace & Truth, Fellowship Friday, Looking Up, Faith filled Friday, Weekend Brew, Still Saturday, Faith and Fellowship,…

- Streams In The Desert- A Guest Post with Abby Breuklander - Precepts & Life Preservers - […] today with other lovely bloggers with hearts for Him at Jennifer Dukes Lee’s linkup #TellHisStory!!! Will you join us?…

- 2 Steps to Remember in the Face of Rejection - […] Linking with others proclaiming the name of Jesus at Me, Coffee, and Jesus, Purposeful Faith, and Jennifer Dukes Lee. […]

- love your now | - […] with Mom2Mom, Hip Homeschool Moms, Soli Deo Gathering , #tellhisstory, […]

- Find the weird one - […] at #TellHisStory, Soli Deo Gloria Sisterhood, #Small Wonder, Playdates with […]

- 3 Positive Steps When You Have Zero Energy | Faith Spilling Over... Into Everyday Life - […] these communities: Holly Barrett’s #TestimonyTuesday, Kelly Balarie’s #RaRalinkup, Jennifer Dukes Lee’s #TellHisStory, and Grace and Truth. Check them out for more…

- How Not to Clean Out a Closet | Ginger's Corner - […] Linking with Inspire Me Monday #RaRa Link Up, Coffee for Your Heart, Testimony Tuesday, Tell His Story, and […]

- Home | danisejurado.com - […] Blog Link Ups: Inspire Me Monday Grateful Heart Testimony Tuesday Raralinkup Coffee For Your Heart Tell His Story […]

- What really frightens me… is that this was nearly twenty years ago. | J.C. Morrows - […] the post I mentioned earlier which can be found HERE in mind, the wondering goes even further. How can so many…

- Trials, Troubles and Tribulations. What Do You Do? - This Day - God's Way - […] Linking up with Holley Gerth’s CoffeeformyHeart, Jennifer Dukes Lee TellHisStory […]

- 9 Secrets to a Life Worth Celebrating | Faith Spilling Over... Into Everyday Life - […] #TestimonyTuesday, Kelly Balarie’s #RaRalinkup, Jennifer Dukes Lee’s #TellHisStory, and Grace and Truth. Check them out for more […]

- Contempt, Comfort & Compassion (Fair Trade Friday) - Katie M. Reid - […] is what Jennifer did the other day. Did you read, “What It Really Means to Have Compassion”? Please […]

- Killing Fear - Purposeful Faith - […] Linking with Holley Gerth and #TellHisStory. […]

- Nice Girls’ Manifesto - […] Crystal at Intentional Tuesday, Kelly at #RaRa Linkup, Holly at Testimony Tuesday, Jennifer at #TellHisStory, Holley at Coffee for Your…

- How to lead people further faster with an often neglected quality - […] To lead with kindness, a leader must use compassion to reach the heart of those who are hurting. […]

- {Guatemala} Building a foundation & threading love - […] linking up with the Soli Deo Gloria Gathering and Jennifer Dukes Lee’s #TellHisStory.Want more insights? “Peace in the Process: How…

- our help when we are overwhelmed (Psalm 142, part 3) | Abounding Grace - […] Musings, Good Morning Mondays, Titus 2 Tuesday, Tell It To Me Tuesdays, Coffee for Your Heart, Tell His Story, Wednesdays’…

Oh, Jennifer, so powerful and sobering. Compassion is a verb indeed. Thank you.

So convicted today by that photo. Thanks for reading along.

Just wow. I’m teary-eyed by this.

Thank you for sharing this today. ((hug))

Thanks for reading along, for sharing my heart.

I am speechless at this post…every word. Maybe just this my heart is crying. Powerful, sobering, convicting. Thanks.

Heart crying with yours, Dawn.

Truly stunning, Jennifer. I’ve never seen this image and am haunted but grateful you’ve brought it to my eyes. Love the idea of picking them up… this one won’t leave my heart for a long time.

Mine either, Anna. xo

That iconic photo and the story behind it is despairing for so many reasons. But you’re exactly right . . . as soon as I wonder why the photographer did not, my own heart quickens as my own did nots. Thank you for sobering words.

Yes. Sobering and convicting.

Tears running down as I read this heartbreaking yet beautiful story, Jennifer. Thank you.

Yes. Tears as I wrote. Heart-wrenching, isn’t it?

Oh, Jennifer – I have no words. Indeed, this is a picture for 2015.

Yes… Thank you for being here, Ellen.

I don’t know what to say, but “wow.” There are so many layers to these words, but I walk away grateful that God has picked me up and charged with extending that grace to others. You are so right – we race right by so much need in the every day – so many who just need someone to extend a hand. Praying for eyes to see it and obedience to put compassion into action. Thank you, Jennifer.

I’m charged, too… feeling the call to keep my eyes ever-open.

This is sooo heart wrenching, Jennifer. Thank you for this powerful plea to us to be picker-uppers.

Thank you, Trudy.

Thank you for this. For letting all the emotions sink into your own heart, for allowing them to mold into a deep conviction, and then turning that into a call to action…for yourself, and for the rest of us. Yes. May we never pass by one who God is calling us to pick up.

Let it be so….

I’m thinking of those in my life who need picking up. Thank you for these good, hard, and hopefully life-altering words.

Oh, this strikes a chord deep in me, especially on the heels of being in Guatemala last week. God’s giving me such a new perspective on compassion and I’m so grateful for your words here being part of that.

Oh, Jennifer, this is truly overwhelming. I’m in tears. Agreeing with the others; it is sobering, touching, convicting, and powerful. My heart aches to see or think about this. Where have I failed to pick someone up? Lord, forgive me! Thank you, Jennifer, for these most precious words of your heart. Bless you!

The wave of emotions crashed on me through this post, Jennifer. (Shaking my head, and releasing a heavy, breath…) I’d not seen the picture before today, nor did I know the story behind it. Wow. Your words dancing with them were impactful to say the least. Now to pray on what to do with it, because certainly the words can’t fall without action. Praise God for your call to action.

That is such a powerful story Jennifer. I don’t know why I’ve never heard about this before now. Thank you for sharing dear lady and for the opportunity to share here each week.

Blessings,

Patti

My eyes were filled with tears as I finished reading your article on “The Struggling Girl.” I am guilty of being too complacent and out of touch with the suffering of many people who live on the fringe of life, struggling for survival and hope. I know this photo will haunt me and yet give me compassion and care for those who need a helping hand, a praying heart and loving actions.

Jennifer, like others here I had not heard this story before and it pains me to see how relevant it is today, over twenty years later. So many times I have turned my head but God is calling me to open my eyes and notice those around me who need to be carried. Thank you for calling us to action. The words he’s placed in your heart will not return void.

I have not seen that photo in years and had forgotten about the photo, the reality, the horror. God will show me those I am to pick up, if I will only look and be available in His time.

Thank you for pointing to the truth that we must act on love and compassion–not just feel it. Praying that this call to action will inspire kindness, empathy and availability in each one of our lives.

I didn’t know the story behind that photo. So many times I’ve been guilty of not picking up the child. We have THOUSANDS of Syrian refugees in our city, on street corners, everywhere. My kids taught me a lesson last fall: they gave a benefit dinner to raise money. The same month my son had to turn in university apps and take the ACT. My first response was “it’s not a convenient time.” But they were convicted that they needed to help refugees NOW. There’s never a convenient time.

Wow! Thank you, thank you very much for this wake up call. I need to keep my eyes open wider to be more intentional. Summer has a way of turning me inward and less outward. Blessings! Love Rachael

Excellent commentary surrounding this timeless photograph, pointing out that compassion without action is moot. The children and their innocence not be lost, to suffer neglect and abuse in this day and age is a crime that often goes unaffected by those who can. We MUST act—even if we think it makes us presumptuous or take on an image not desired. ACT! God Bless the soul of this child and of the man who failed to pick her up when he could have. Thank you for telling this story.

Such a haunting photo. I remember seeing it years ago, yet I find it even more disturbing in these days. I’ve been that child…not physically, but spiritually. So weak from my sin, and so malnourished from the lack of the God’s Word that Satan the vulture waited nearby. I’m so thankful that Jesus did pick me up. Blessings to you, friend.

Heartbreaking stories and photos. I can’t believe we complain about internet connections or too much of something in our food while people out there suffer like this.

May I just mention how much Michael Jackson had done to help save children like these when he was alive. I hope more people could follow his lead.

When we see people suffering we wonder where God is. And the answer is in all of us. We need to be Jesus to our brothers out there.

This hurts my heart. I had seen the image before, but did not know the background or the story of the photographer.

Thank you for this, Jennifer. I needed these words this morning. I needed the reminder…Open my eyes, Lord.

Love you.

Jennifer, this just moved me to tears. I remember seeing the photo before. I never heard the back story. Praying for God to open my eyes every day & move me to compassion like His. Thank you for this post.

Wow, just wow. I am in tears, Jennifer. This is a powerful piece. And not only for the image which is a shocking portrayal of suffering, but for your words – for your call to action – that we might live lives of genuine compassion – to carry the hurting, and suffer alongside the broken. I have prayed, just now, that many would read these words, and that hearts would be broken for the things that break the Father’s heart.

Much love,

Kamea

Thank you for bringing this photo to all of us. May we be stirred to not leaving anyone behind through our actions, words and love.

oh…Lord have mercy…may we act with compassion as God leads and may we be willing to suffer with…Thank you, Jennifer…Have you heard of Pastor Saeed Abedini, the American pastor who has suffered in an Iranian jail for over 3 years….http://beheardproject.com/saeed?utm_medium=Email&utm_source=ExactTarget&utm_campaign=bh#sign

Lord have mercy. So many to pick up. And the news this week that they are selling the body parts and organs of aborted babies, right here in our backyard. WHO WILL PICK THEM UP? We must rise up and write words and speak truths. We are the Gospel bearers. Oh God help us all.

Wow! This post is very moving. Makes me think about so many adults functioning on the outside, yet still a broken, wounded child on the inside – just wanting to know they are wanted and loved. There is brokenness all around us and hurting children come in all shapes and sizes. May God open our eyes to see and reach out as He heals our inner child. We all need healing and we all can be His hands and feet in this world no matter how broken we are.

Wow. Takes the picture of compassion and makes all of stand up and listen. Thank you for sharing this story. Blessings, Chris

I don’t know how I’ve never seen this photo before or heard the story behind it. So heartbreaking. Thank you for the reminder to never just walk on by but to be the Savior’s hands and feet.

One of the most moving post I have read on compassion.

Heart-wrenching. Soul-piercing. God, don’t let me miss an opportunity to pick up a child (no matter the age) and bring him/her to you! And bless Jennifer, I pray, for her compassionate heart and passionate spirit that inspires us all.

Wow! This is brought me to tears. I live in a county in our nation that has the highest poverty rate in America. Sometimes we become calloused as a means to stop the hurting from seeing so much suffering. I needed this reminder to open my eyes as well as my heart. I want to have compassion not only in thought but in action. Thanks so much for such a great post!!

Oh Jennifer, This is why you write, because it moves people to compassion, conviction, and action. Thank you for carrying her to us, for carrying His words.

Oh Jennifer, This is why you write, because it moves people to compassion, conviction, and action. Thank you for carrying her to us, for carrying His words.

Lord, have mercy on our hard hearts. Open our eyes to the need in front of us.

This is an amazing article. Thank you for sharing this photo and your thoughts. I’m truly moved and hope to pick someone up today. I did think that compassion was a noun though, not an adjective, but I love the idea of it as a verb.

Thank you, Rochelle. I appreciated your response and your correction. How on earth did I call compassion an adjective? I have fixed it. Thanks for grace!

Very moving story and post. Thank you for sharing. Though I do wonder why you wrote “Compassion is a noun, but in the heart of a Christian, it ought to be a verb.” It should be in the heart of anyone! Why say Christian?

Hi Donna! Great question! Maybe you’re new around here? If so, a hearty welcome to you. My blog (on the internet since 2008) is primarily designed to reach and challenge a Christian audience as we live in this world as followers of Jesus in this age. So, while I would hope that all of us would show and practice compassion, regardless of our faith backgrounds, I’m specifically challenging Christian followers to live as Jesus lived … to live a compassionate life.

Thanks for being here! It’s been wonderful to meet so many new readers through this post.

~ Jennifer

So powerful, poignant. I hope I don’t forget that in my work for Christ I need to look around to see who needs picked up and rescued. We get so caught up in the words, writing, and photography, we forget God has a purpose for us and people that He wants us to reach. I pray I don’t let them down.

There is another version of this story. The child’s parent was at the food truck getting food for this child. The photographer recorded this moment and made us aware in a very graphic way of the plight of the people of Sudan. It is a very powerful image as well as a powerful back story. We were not there, we should remember not to cast any stones as we lift each other up.

I also searched the web looking for the truth behind this photo. I did read that the parents were nearby getting food from the plane and that the photojournalists were told not to touch any of the people for fear of spreading disease. It said that even if he had picked the child up there was not much he could do to help. His full statement on his suicide note said, ““I am depressed … without phone … money for rent … money for child support … money for debts … money!!! … I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain … of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners … I have gone to join Ken [recently deceased colleague Ken Oosterbroek] if I am that lucky.” I agree with not casting stones.

Yes, same here… the whole story os one that teaches compassion, not only for the child but for the photographers doing the job.